MADISON COUNTY, Ill. — With nine weeks to go before the 2022 midterms, local election officials across Illinois are fielding a new wave of baseless grievances and impossible demands from 'election integrity' activists who insist the 2020 presidential election was stolen.

In recent weeks, a variety of form letters and emails, most of them including the same language, started arriving in county clerks' inboxes. The letters often came as open records requests filed under the state's Freedom of Information Act law, but they included incoherent demands or inaccurate lists of data the clerks don't collect in their election counting processes.

"I do not have the type of data that they're asking for," Madison County Clerk Debbie Ming-Mendoza told 5 On Your Side. "This is a no-brainer for me. If I don't have it, I can't give it."

Dan Tang, Madison County's deputy clerk, showed our cameras how the vote tabulators work, and explained why the data the activists sought isn't kept in the machines.

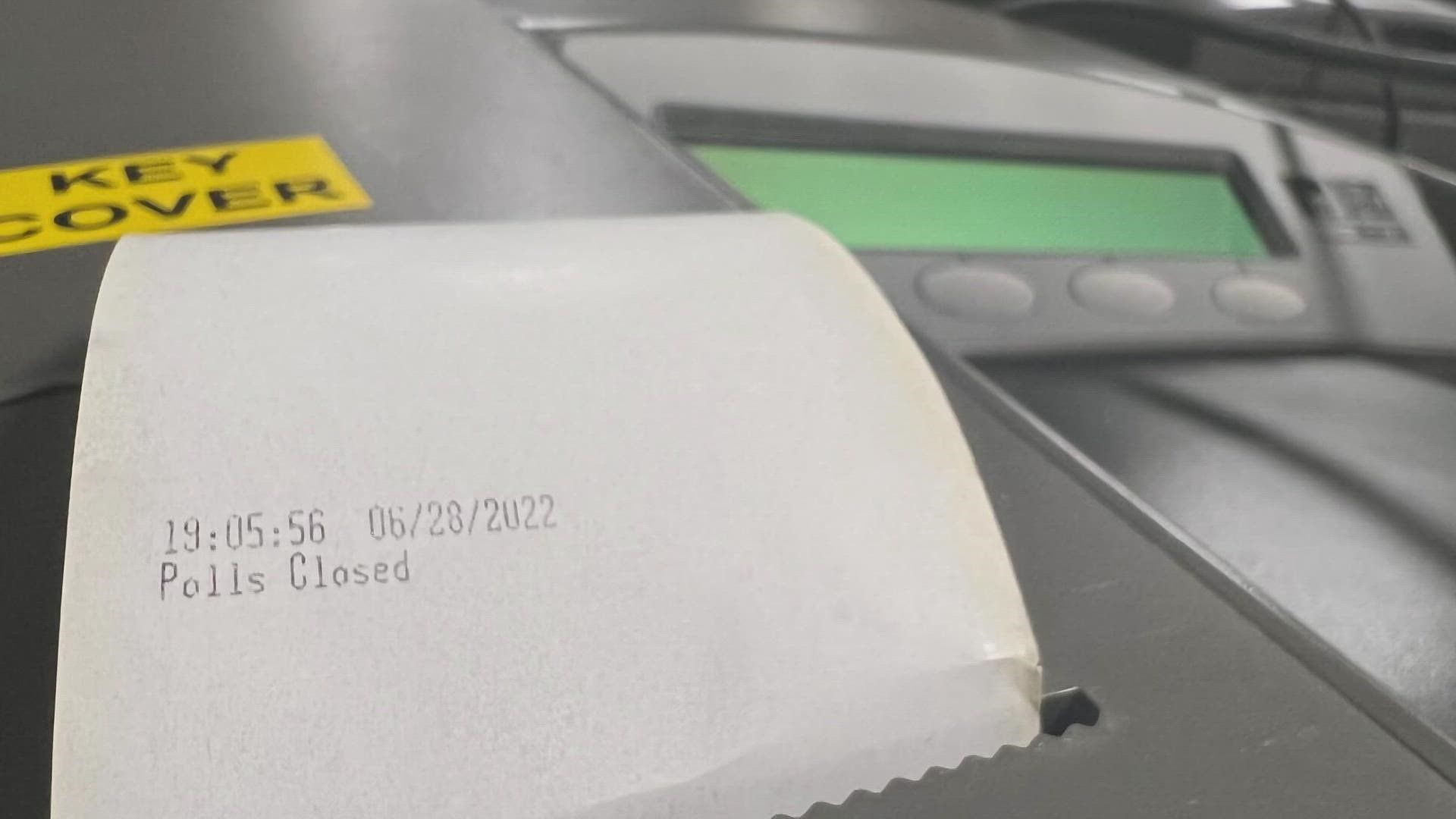

He said the vote counters cannot connect to the internet, and only start tabulating the final vote count for each candidate once a marked ballot passes through the scanner. Each machine is zeroed out before the polls open, and each machine tabulates the final results after polls close. The vote-counting machine will not count a ballot that doesn't correspond with a voter in that precinct, but the device doesn't keep a written record of how each person voted. That evidence exists only on the paper ballot itself.

"They create a FOIA that no one can comply with," Tang said. "And since no one can comply with it, maybe that's their ammo to say, 'Look, there's a problem here.'"

"They don't make a lot of sense," Illinois State Board of Elections spokesman Matt Dietrich said about the letters. "They're sort of copied and pasted."

In Illinois, President Biden won by more than a million votes. Still, election skeptics are claiming they will eventually bring a lawsuit that proves their theories about widespread voter fraud.

"I think it's kind of a ridiculous thing to say that the election was stolen," Tang said. "Because it's obvious to me that it wasn't."

John Ackerman, the Republican county clerk in Tazewell County, said his office received "five or six different form letters."

"One is demanding we don't destroy ballots" from the 2020 election, he said.

Michelle Turney, a former Chicago police officer who failed to collect enough signatures to appear on the 2022 primary ballot, sent an email to the Iroquois County Clerk's office under the subject line "Class Action Lawsuit."

"I am contemplating filing suit against your organization based on credible information I have received regarding your organization's possible involvement in criminal and/or civil actions pertaining to election integrity issues," Turney wrote.

Later, in the same email, she told the local election authorities who work in a county two hours south of her hometown that she was their employer and threatened them with criminal consequences.

"I AM CONSIDERING SUING YOU FOR YOUR AND/OR YOUR ORGANIZATION'S INVOLVMENT IN THE FRAUDELENT (sic) ELECTIONS THAT WILL SOON BE PROVEN TO HAVE TAKEN PLACE SINCE 2017," Turney wrote in all capital letters. "Any attempts by you or your organization to destroy the election records and accompanying relevant documentation that I, as your benefactor and employer, have demanded you retain will be met with the harshest possible criminal and civil repercussions available under the law."

Illinois state law requires county clerks and election authorities to maintain paper ballots for 22 months following an election.

"Those ballots can only be unsealed by a court order," Dietrich said. "That's designed for a recount."

"We're not seeing any seriousness or pending litigation," Ackerman said. "We're disregarding it in Tazewell County."

He said they would move ahead with plans to shred 2020 ballots soon.

Mendoza confirmed that her office notified authorities about an attempt at voter fraud during the 2022 Democratic primary.

"I did my job," she said. "I did what the voters expect me to do. And when the [election] judges brought the concern of the handwriting to my attention, I reported it immediately to the state's attorney's office."

State's Attorney Tom Haine referred the matter to a special prosecutor and described the matter as an ongoing criminal investigation.

"It's a perfect example of the system working," Mendoza said, "because those ballots were not cast."