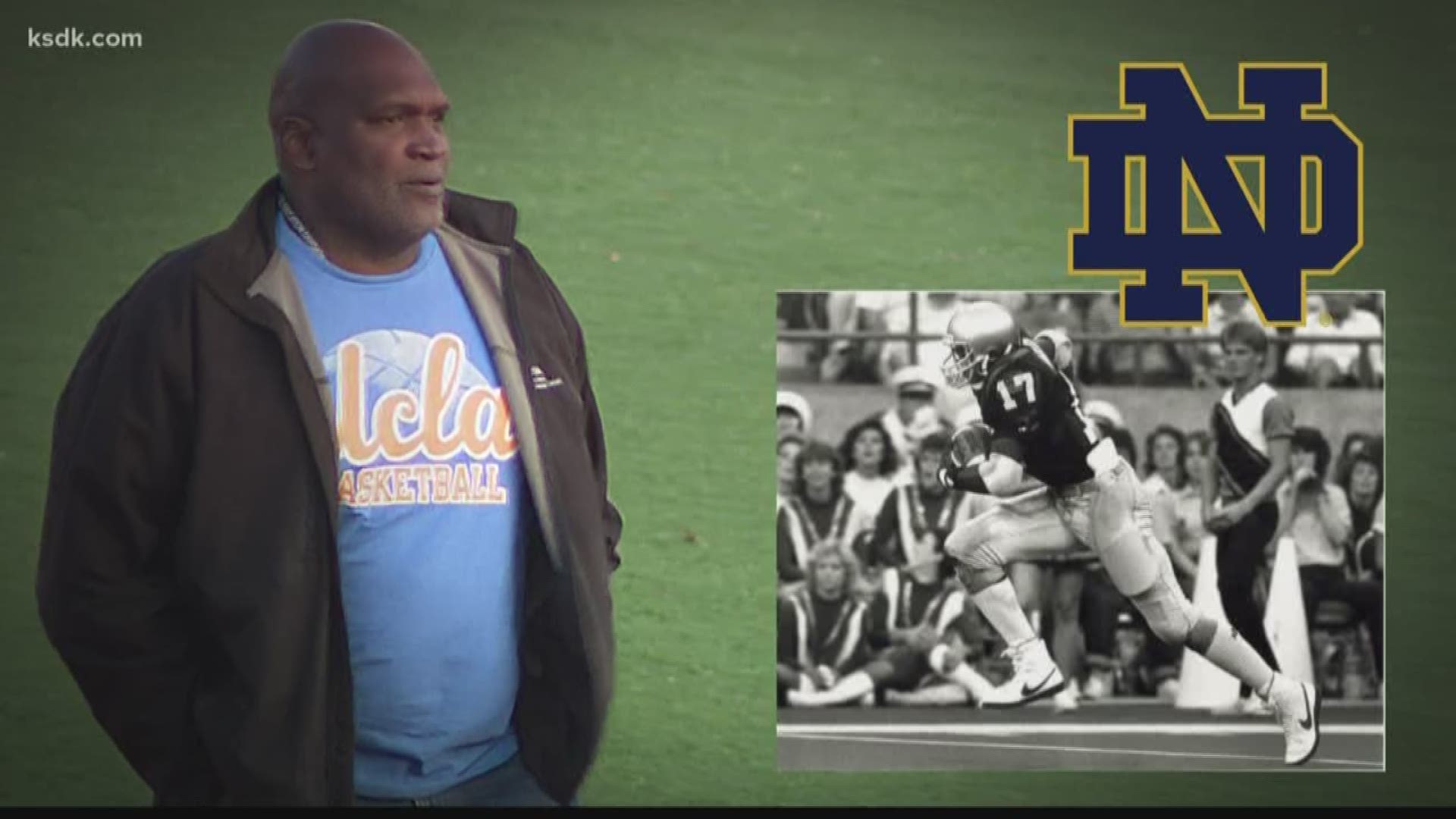

ST. LOUIS — He is as much a part of Kirkwood High School as the Pioneer mascot itself. Go to any Kirkwood game and you’ll find Alvin Miller there.

Even when he’s not, he still very much woven into the very fabric of the community culture.

In January of 1983 Miller was named as Parade Magazine’s National Prep Football Player of the Year. Video from that era is evidence why. He had the long, loping strides into the secondary, great hands, and was darn near impossible to bring down. That’s a fact of which he is proud of to this day.

“My goal in football was not to get tackled, and there’s not too many guys in St. Louis who could say they tackled me,” Miller recalled.

He ran track as well, and people still talk about the day he led the Pioneers to the state title, winning four events by himself. He says he didn’t follow a strict training regimen that day.

“You probably shouldn’t have too many ham sandwiches from Mom, or two or three Cokes before a track meet," Miller said. "My brother was my coach but since my mom made my lunch he didn’t say too much.”

Over thirty years later, Alvin still holds the school records in the 100 meters, the 200 meters, and the 110 high hurdles. The track at Kirkwood was named in his honor in 2012.

To add to his resume, he also lettered four years in basketball. Safe to say that he was well known to college recruiters.

“It was easier to say what school didn’t offer me a scholarship. I didn’t get a scholarship from the University of Montana or Slippery Rock," Miller said.

Many of the school’s student body came to watch Miller sign his national letter of intent to play at Notre Dame, a testimony to his popularity among the student body.

So what happened to Alvin Miller on the road to glory in South Bend, and then in the NFL?

To skip ahead, Miller did catch a touchdown pass in the Liberty Bowl as a freshman. That was one of only 22 catches he made as a Golden Domer, as knee injuries derailed his path to pro glory.

And yet, Miller still views his life as a success.

That’s not an outlook many athletes in his situation care to share. Instead, they view the millions of dollars lost, the fame and notoriety that dried up, the settling for a life much different than the one they had planned for themselves.

That is the turning point many athletes have to face. Yet, for Alvin Miller, he says his turning point came before he even put on the gold helmet of the Fighting Irish.

Instead, Alvin’s moment came off the field, between the locker room and the gridiron. It was a moment he didn’t orchestrate, but rather was presented to him by a teammate on a walk off the field after practice. Alvin remembers the exact spot.

Wayne Cooper, a football and track teammate of Alvin’s for several years, stopped the future star in his tracks when he told Miller that he was on par with a pair of dazzling NCAA stars of the time, Oklahoma running back Marcus Dupree and Georgia Heisman Trophy winner Herschel Walker.

“I didn’t watch college football, but he had seen those guys play,” Alvin said, “and for him to say that made me think, ‘Wow.”

Alvin has a picture of Cooper running a four x 100 relay leg, taking the handoff from teammate Keenan Curry which he calls “the greatest handoff ever."

Cooper never saw his friend reach the national spotlight. He died before graduating from Kirkwood. However, Miller says he took Wayne with him every day after that. When he scored his touchdown against Boston College in the Liberty Bowl, a national television audience saw him kneel and say a prayer.

“I never told anybody, but it was in memory of Wayne that I took a knee, Miller said. "No one ever asked me, they just assumed, but that was more or less to pay homage, and so I took a knee and a moment of silence in his honor.”

And so how was the comparison to a pair of famous collegians worthy of a life-altering moment?

Miller says it fueled in him a desire for excellence that he carries thirty years later. It was a quest to achieve that, as one of eleven children, he already had to have.

“I would always say I don’t want to be one of the best. I want to be the best," Miller said.

That desire led him to run sprints and drills by himself in the hot summer days after the school year ended. It pushed him to attend a university with a high academic expectation, and get his degree.

“I tell kids all the time, if you don’t get that piece of paper, that pro contract, make sure you get that piece of paper, that college degree," Miller said. “They never tell you to go to the library, but you have to think about that forty-year decision.”

He reminds the kids he talks to that pushing to get your college education, and even choosing the right school, is a forty-year decision, not a four-year decision.

(It should be noted that while Walker went on to the fame and glory predicted for him, Dupree, like Alvin, suffered a career-altering injury and never reached the stardom many expected him to have. ESPN Films did a great 30 for 30 documentary on Dupree’s post-football life, “The Best That Never Was.”)

Miller said his desire for excellence helped him to redefine what life success is for him. He doesn’t see failing to make it to the NFL as such. He calls his life as a businessman, community leader, husband and father, a successful one.

Miller is writing a book about his experiences, offering life advice stemming from his memories and the people who touched his life. As one example he likes to share with youngsters dreaming of dollar signs is another Kirkwood athletic great: former Mizzou and NFL star Jeremy Maclin.

Maclin, who now spends time giving back as an assistant football coach at Kirkwood, did make it to the NFL and achieved wealth and notoriety, but that too was cut short due to injury. And yet, Miller said, “Jeremy Maclin would be a success even without football. Smart kid.”

A turning point can often generate a climb to greatness, or produce a moment that is remembered forever. But often, that turning point can also be a subtle nudge on to the path of life success, a success that we and only we can define.