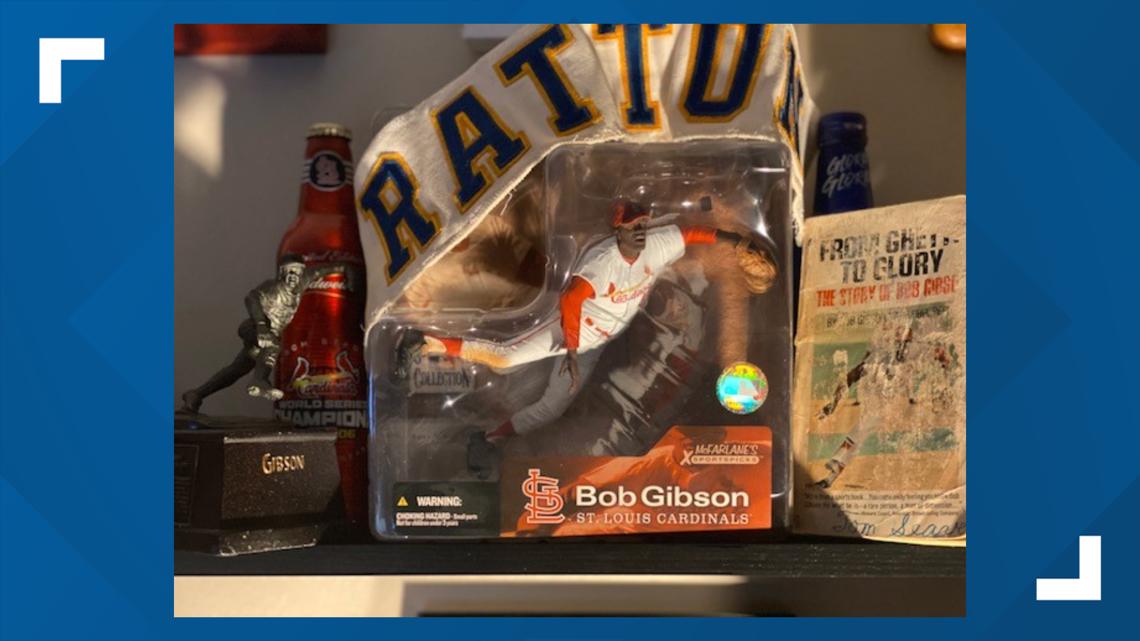

ST. LOUIS — A book, a scorecard, an action figure and the real Bob Gibson.

When we lost Lou Brock last month, it was like a punch to my gut.

Hearing Bob Gibson passed a few hours ago was a shot straight to the heart.

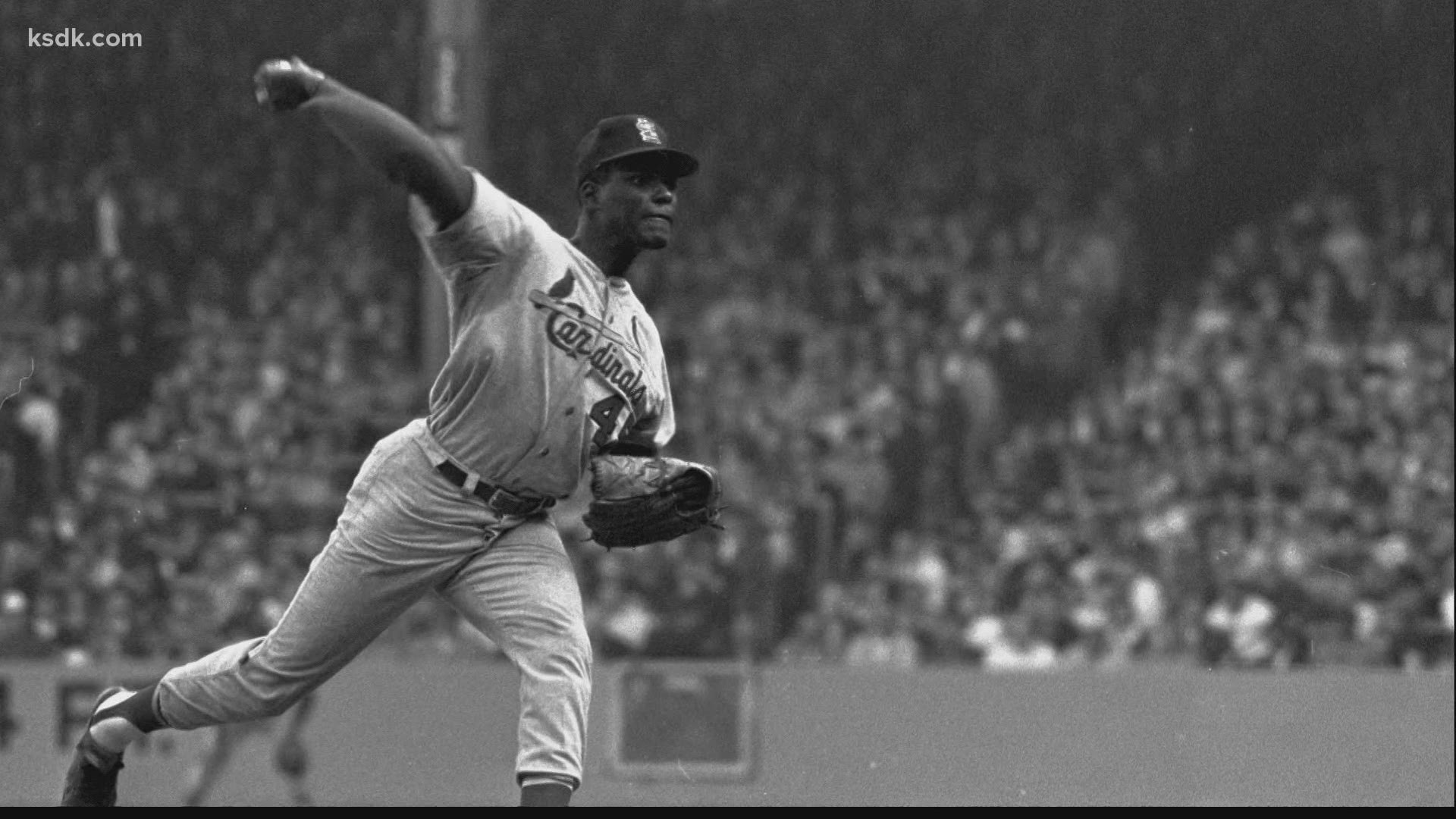

And in some kind of macabre sense of timing, he died 52 years to the day of his most memorable pitching performance: Game One of the 1968 World Series.

Seventeen strikeouts.

Still a record.

(Sigh)

Oh, I’ve had over a year to face the reality that one of my ultimate sports heroes was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer – and no one has beaten that vile beast yet. But I thought if anyone could, it would be Bob Gibson. I guarantee you this was no knockout, or even a unanimous decision; Gibby lost on a split decision and he took it to the limit.

I heard Gibson’s former teammate Dal Maxvill explain him this way: he gave 100% on every pitch. Some guys will bring their full measure when they need to or in a tight spot, but Bob Gibson gave his all on every pitch!

Imagine that.

He gave no quarter and asked for none in return. He’d just as soon knock you down with a pitch rather than see you trying to dig in in the batter’s box. His pitching philosophy? “Half of the plate is mine; your job as the hitter is to figure out which half.”

So why the reference to the book and the scorecard and the action figure? Bob Gibson means an awful lot to me, and each of these objects represents family – at opposite ends of my life.

THE BOOK AND THE SCORECARD

Thanks to my mother I developed a love for the Cardinals; I’ve written several times about how it was mom, and not my father, that was the sports fan in the family. I have distant memories of my mom listening to the Cardinals on the radio in the afternoons. She loved Harry Caray and she loved her Cardinals.

When I was in the second grade, I had learned how to read early in life thanks to mom. I also was kind of sickly. Anyway, I spent a couple of weeks in the hospital right before Christmas with pneumonia. Spoiler alert – I recovered – and I remember that mom andd brought some books for me to pass the time.

One of them was the recent Bob Gibson autobiography, “From Ghetto to Glory,” and it wasn’t easy to plow through or understand a lot of the adult topics he talked about. But I was enthralled as he described how he pitched to a lot of the big-name hitters he faced – that was kind of gutsy in retrospect, since he would face them again after the book came out. But that, as I would learn, was Gibson to the hilt. Matter of fact, blunt and honest to a fault.

I also was shocked to read about how he broke his leg and continued to pitch! A Roberto Clemente line drive cracked a bone around his ankle, and three batters later the bone snapped as he was following through. The accompanying photo looked like it really hurt. (Note to younger self: It did.) And yet, six weeks later he was back on the mound. Somehow I think reading that made me try a little harder to get better. Well, that and trying to get home in time for Christmas.

As Gibson wrote, he came back to pitch in that 1967 season, ultimately winning three games in the World Series. I have a memory of my mom being excited one day, excited because she was going to go see the Cardinals play that night – I think with my aunt and uncle. I begged, pleaded, cried, threw a fit and was otherwise a brat because I wanted to go, too. I didn’t quite get the idea about having to have a ticket, that they had three tickets, and they didn’t have four. So, I stayed home that night with my dad. I have no idea if I listened to the game on the radio or if I ever stopped being mad about not getting to go. I think my mom said she would bring me back something from the ballpark. If I was good.

Too late.

Bob Gibson made five starts that September as the Cardinals were already far ahead of the pack in the National League, even without their ace for that long period. He came back against the Mets, pitched shutout ball against the Phillies and then pitched a complete game in Philadelphia as the Redbirds officially clinched the pennant. Then two more starts had him finely tuned to overwhelm the Boston Red Sox.

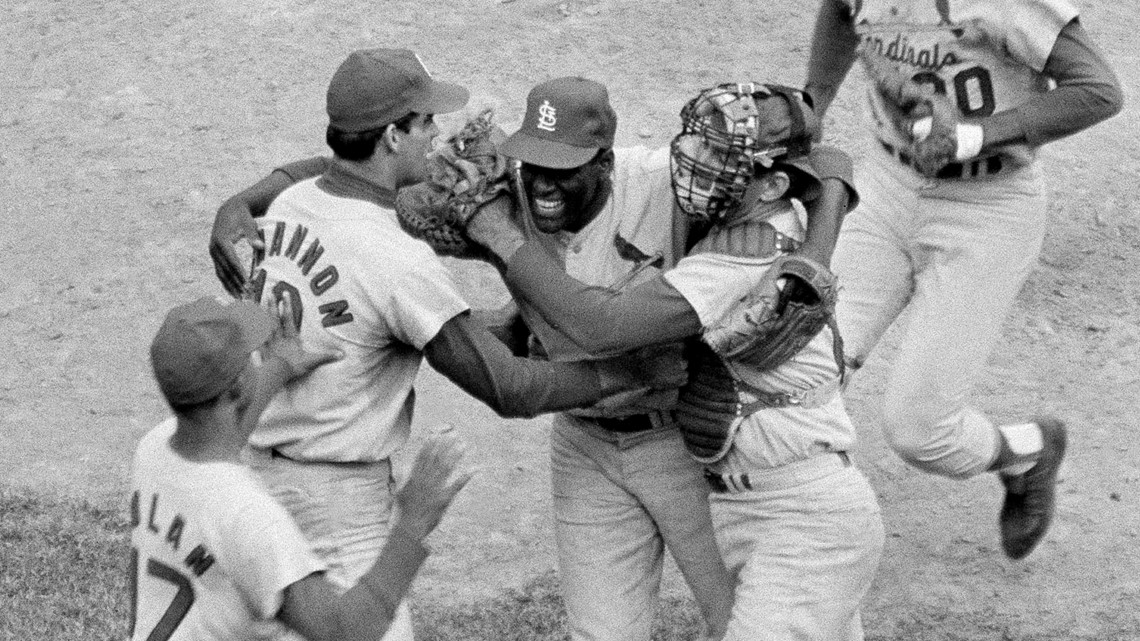

Gibson was the Series MVP.

My mom passed away a couple of years after that when I was eight. Some years later, as I was going through some things she had tucked away in a cabinet in my room I came across a scorecard. In my mom’s handwriting was the date on the front: September 12, 1967. I looked inside to see who played that day. (A little story for you young folks that might be reading: back then, they printed the expected lineups for the two teams on the scorecard but often times the P.A. announcer would list “corrections” to what was on the card. Nowadays they just sell blank scorecards and leave the filling out the lineups to the fans.)

As my eyes panned down the Cardinals’ page, the pitcher was listed as “Gibson 11-6.” Bob Gibson pitched that game! What’s more, I added up the equation that the scorecard I was holding came from the game my mom, aunt and uncle went to after I threw my titanic fit for not getting to go.

She did bring me something home.

As I got older, I was able to do more complicated math; like, could that game have been one of those starts Gibson made after coming back from his broken leg? It was one of those math problems like you had on a test in school: you had the right answer, but it was marked wrong because you didn’t show the work.

The more I thought about it, it had to have been one of those games, but I had no way to prove it – until a lot of years later and voila! Internet, and more specifically, Retrosheet.org. Someone had actually taken the time to find all those old box scores and had the actual play-by-play of what happened! I looked up the date, and sure enough, I was right all those years ago. I have that scorecard in a special place, with the printed Retrosheet box and play-by-play tucked inside.

I embrace anything that connects me to my mother, even 50 years later. Thank you, Bob Gibson.

THE ACTION FIGURE

When my son was 13, he had heard me refer ad nauseum to Bob Gibson and other athletic and historical greats. Gibson was someone I always hoped my stories of how competitive he was, how he never backed down and how he had overcome so much in his life to get to where he was, would leave an imprint in my son’s mind.

It probably did up to a point. At the age of 13, many kids begin to think their fathers are idiots and tune them out. Why would John be any different?

I mean, I relayed stories I’d learned over the years – how, for example, he’d set the record for strikeouts in a World Series game, and as his catcher and close friend, Tim McCarver, came out toward the mound to point out the record that he’d set was on the scoreboard, Gibson told him to get back behind the plate. Another time McCarver came out to try and offer words of wisdom, only to have Gibson tell him, “The only thing you know about pitching is that it’s hard to hit.”

I enjoyed the funny ones, but I also told him how Gibson had grown up poor and sickly – how he’d been bitten on the ear by a rat in the housing project his family had to live in for a time. How he never knew his father. How he’d been denied going to the college of his choice because of the color of his skin. How he’d been slowed in his development by a manager who stereotyped him as a thrower but not a thinker or a real pitcher on the mound. How he’d been fueled by the anger over the deaths of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy to have the greatest season any pitcher has had in the live ball era. How the Cardinals were so far ahead of their time in terms of racial harmony: Whites, Blacks, Latinos all close friends in a time of unrest – lessons we still struggle to learn a half-century later.

Back to McCarver. He was a young and naïve native of Memphis when he came to the Cardinals; Gibson was several years older and perhaps decades wiser. The noted author David Halberstam relates a story that the team was riding on a bus during spring training and Gibson decided to mess with the young catcher as he was drinking from a bottle of orange soda. “Hey Tim, can I have a drink of that?” McCarver got uneasy, not knowing how to respond. Finally, he said “I’ll save you some.”

From that grew a deep, enduring friendship, and long conversations that fostered understanding, mutual admiration, and brotherly love. If you can find that kind of friendship in your life, I told my son, you will have lived well.

That 13th year of my son’s life, a friend and I took our sons on a baseball pilgrimage – four games from Chicago to Boston. I could regale you with details of how great a trip it was, but I’ll stop at one. We made an unplanned stop at the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown. We got there about mid-afternoon and the Hall was closing at 5 or 6 p.m. I had just been there a couple of years earlier to help with our coverage of Ozzie Smith’s induction ceremony, but that day was like I’d never been there before. I was mesmerized by the exhibits and the history there right in front of me. The tables were turned, and it was my 13-year-old who was looking back at his father and practically yelling at me to keep up the pace.

After he had finished going through the Hall, he told me to move it along, but in the meantime he’d be in the gift shop. I didn’t really think too much about it but by the time I caught up with him he’d made a purchase. We left and headed on our way to continue our journey. I think it was a couple of days later, John gave me the bag from the Hall of Fame and thanked me for the trip and the great time. I opened the bag and there was a Bob Gibson McFarlane action figure, Gibby in full follow through.

That tornado-like delivery of Gibson’s was a sight to behold. He loved to work fast and often would be ready to throw the next pitch as soon as he got the ball back from the catcher. Then he was into the windup again, twisting, spinning and pivoting before violently firing the ball toward the plate – so violently and using every fiber of his body that he would land with such momentum, it left him in a completely awkward position if the ball came back through the box. And yet Bob Gibson won nine consecutive Gold Glove awards for fielding excellence. How did he do that?

He was such a great athlete that he could have probably played in the NBA. As it was, he was a 20-points-per-game player at Creighton – still one of the school’s all-time hoop greats. He played for a short time with the Harlem Globetrotters but didn’t like the clowning. As a pitcher, he hit 24 career homers, tied for 7th on the all-time list. In 1970, not only did he win 23 games but also batted. 303.

In the moment, I was really touched by John’s gift. He was very thoughtful, and needless to say he figured out how to give a gift that would mean something. Maybe – just maybe – those Bob Gibson stories made an impression on him, too. I couldn’t have been any more proud of him than I was that day, and that McFarlane figure has never come out of the packaging – it sits with honor on one of the shelves in my office where I can see it every day.

I embrace anything that reminds me of my children. That simple gesture is frozen in time in my mind. Thank you, Bob Gibson.

THE REAL BOB GIBSON

I got to meet Mr. Gibson a couple of times when he came to KSDK. Each time he was genuinely nice, warm and nothing like his mound persona. If I didn’t have work in front of me and if he didn’t have better things to do, I could have been content talking to this man for hours.

I’m reminded of how he completely freaked out Willie Mays, the great outfielder of the 50s and 60s. Part of Gibson’s mound intensity came as he nearly drilled holes with his eyes as he looked to get the sign from the catcher.

Fiery. Intense. Locked in.

Well, the two were at a friend’s house for dinner, and at one point Gibson took out a pair of glasses and put them on. Mays got bug-eyed and asked Gibson, “You wear glasses?!” Yes, Gibson replied. “But not when you pitch?!” Gibson said no. Mays then shrieked, “Man, you’re going to kill somebody!” But that mound expression of Gibson’s was purely him squinting in to see what fingers the catcher was putting down. If it gave him an imposing, mean look and made the hitters think a little bit more, then so be it.

My cordial meetings with Bob Gibson are treasured. He made a point to say that his reputation was overblown, particularly when it came to throwing at hitters. Not true, he said. That was the way you pitched in those times, and if batters chose to stand close to the plate, then that was their choice. Of course, he went on to say that if his career had happened in more contemporary times, it would have been different and probably not as successful. The high strike that Gibson thrived on doesn’t get called anymore. He also thought he’d never pitch a no-hitter because of pitching high up in the strike zone; easier for a hitter to connect and drive the ball for a hit.

Of course, he got his no-hitter. That makes me believe he would have figured out a way to be successful in today’s game.

As for pitching inside; well, he probably would have been a regular visitor to the league office paying fines and being handed suspensions. Still, he would not have backed down and he would have still been successful.

His singlemindedness and relentless drive made it a no-doubter when he became baseball’s first “attitude” coach. Friend and former teammate Joe Torre created the job when he hired Gibby to be on his coaching staff with the Mets and Braves.

Not pitching coach. Attitude coach. Makes perfect sense if you think about it.

I remember Gibson being asked the question that’s often used to close out interviews: How do you want to be remembered?

Gibson gave an answer that was completely original, and in the same way, completely Bob Gibson. He said that he wanted to be remembered as a guy who gave everything he had and never let the fans leave feeling cheated out of seeing his full effort.

Win, lose, or draw, he said, “I didn’t cheat ‘em.”

The world is a lesser place today in his absence.