MISSOURI, USA — Missouri's first modern turkey hunting season didn't open with a bang.

Nearly 700 hunters in 14 counties took part in the inaugural three-day event in 1960, but the turkeys didn't return the favor. Only 94 of the birds were harvested.

That harvest would get blown out of the water decades later. Missouri hunters harvested a staggering 60,744 turkeys in 2004 throughout three seasons, the most Missouri turkeys ever harvested in a single year. For better or worse, that state record remains unbroken.

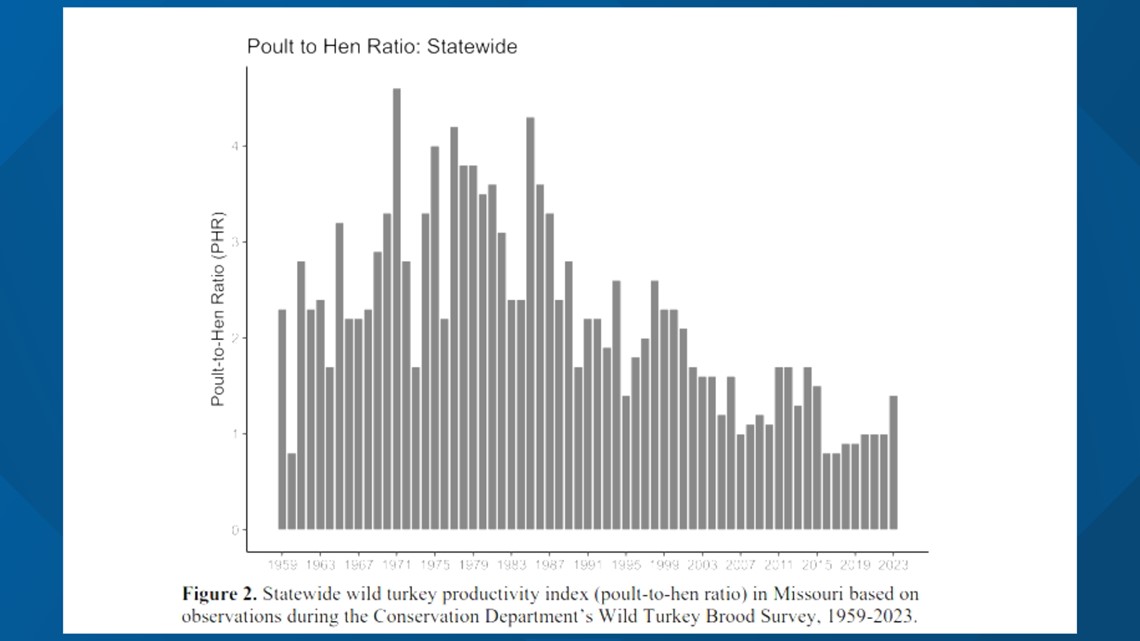

Missouri, and the United States as a whole, have since experienced a wild turkey disappearance. The nation's wild turkey population has declined by around 1 million since 2004, biologists told the Washington Post. Missouri's poult-to-hen ratio, or the number of young turkeys compared to adult female turkeys, has also decreased over the past 20 years.

While a combination of increased hunting, more predators and rising average temperatures could play a role in the birds' decline nationwide, those reasons don't necessarily speak to Missouri's decrease. Changes in the state's land itself may be a more likely culprit, according to Missouri Department of Conservation Wild Turkey Biologist Nick Oakley.

"We have less habitat than we did even in the mid-2000s," Oakley said. "Really subtle things can make a difference."

Some of those things include unregulated forest growth and an increased presence of invasive species, which can drive wild turkeys out of their nests and brooding locations. The birds need a particular type of habitat for around two months of the year to safely birth and raise their offspring, and some of those locations have been lost over time.

"In north Missouri, it's a more interspersed kind of habitat where we've got pockets of trees and pockets of open land where we've lost some of the brush for nesting," Oakley said. "In the Ozarks, it's a lot more wooded, and that's where we see mature old forests no longer being good brooding cover ... that's when we see things like predation become more problematic."

Oakley would love to see forested areas have more woodlands while returning native grasses to the state's prairies, but he acknowledged that these are long-term goals. A sooner boost to the state's wild turkey population, and other wildlife populations, could be seen in the coming years thanks to the state's upcoming cicada brood.

Brood 19, Missouri's largest cicada brood, is expected to emerge in late April next year. Oakley predicts the reemergence may help prop up the turkey population.

"That gives a slam-dunk food resource for not only the hens but also the poults," Oakley said. "I also think [the cicadas] will decrease predation ... everything in the woods will eat cicadas; the raccoons, the possums. Anything that's going to eat a turkey poult will also eat a cicada. So it's a reduction in predation risk."

The last reemergence of brood 19 in 2011 caused the poult-to-hen ratio to increase, according to MDC data. The increase was sustained for 5 years before the wild turkey population dropped again.

Any potential wild turkey increase from cicadas, however, won't be seen until a couple of years later once hunting season numbers are in. Time will tell whether future Missouri turkey hunters will ever see a season that rivals the 2004 season.

In the meantime, MDC offers information to help private landowners create apt habitats for turkeys to live on. Click here for more information.

St. Louis headlines

Get the latest news and details throughout the St. Louis area from 5 On Your Side broadcasts here.