LOUISVILLE, Ky. — August 10, 2020 saw a powerful and damaging windstorm lambast the Midwest. In killed three people in Iowa, one in Indiana, decimated crucial corn crops, and left hundreds of thousands without power for days. It also caused significant damage in parts of Illinois and Indiana.

This rare windstorm is known as a derecho. It’s not a word used often, nor is it a weather event seen often, but it captures headlines when it occurs. Unfortunately, There has been some confusion and misinformation regarding this historic event, namely references to the storm as an “inland hurricane” and that there was “little to no warning.”

What is a derecho?

Technically speaking, the American Meteorological Society defines a derecho as “a widespread convectively induced straight-line windstorm.” More simply, a derecho is long-lived intense wind storm that moves quickly while often producing tremendous amounts of rain. Derecho has Spanish origins and can be interpreted to mean “straight ahead” or “direct.” This word was tactfully chosen to distinguish between damage caused by tornadoes, whose winds rotate, and those from straight-line winds. For a storm to be a derecho, there must be damage (continuously or intermittently) over a distance of at least 400 miles with a width of at least 60 miles.

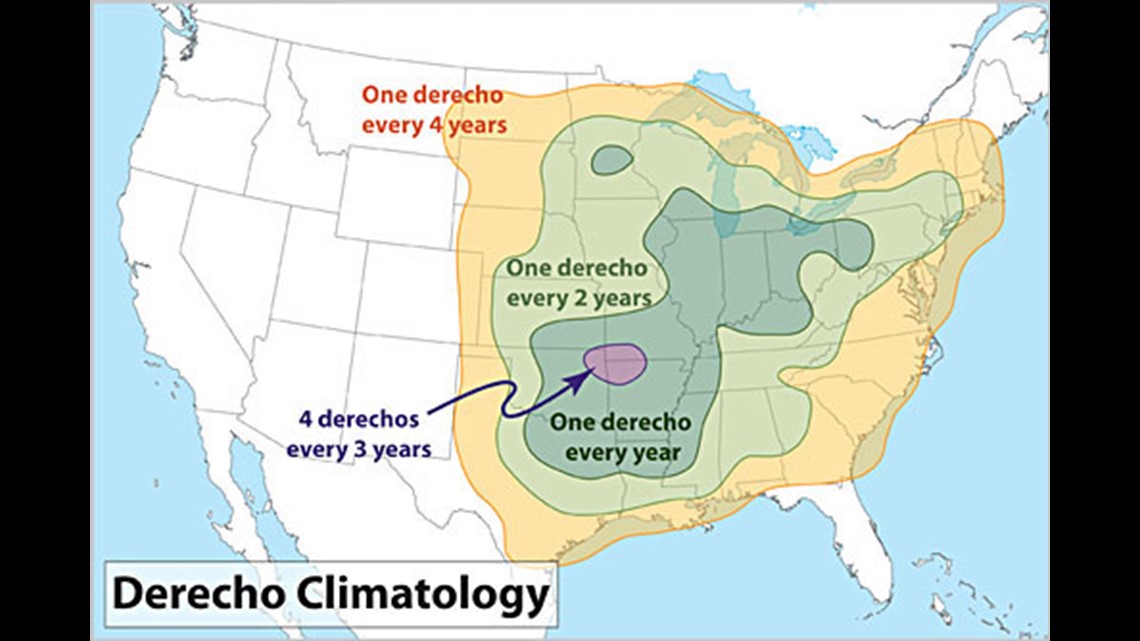

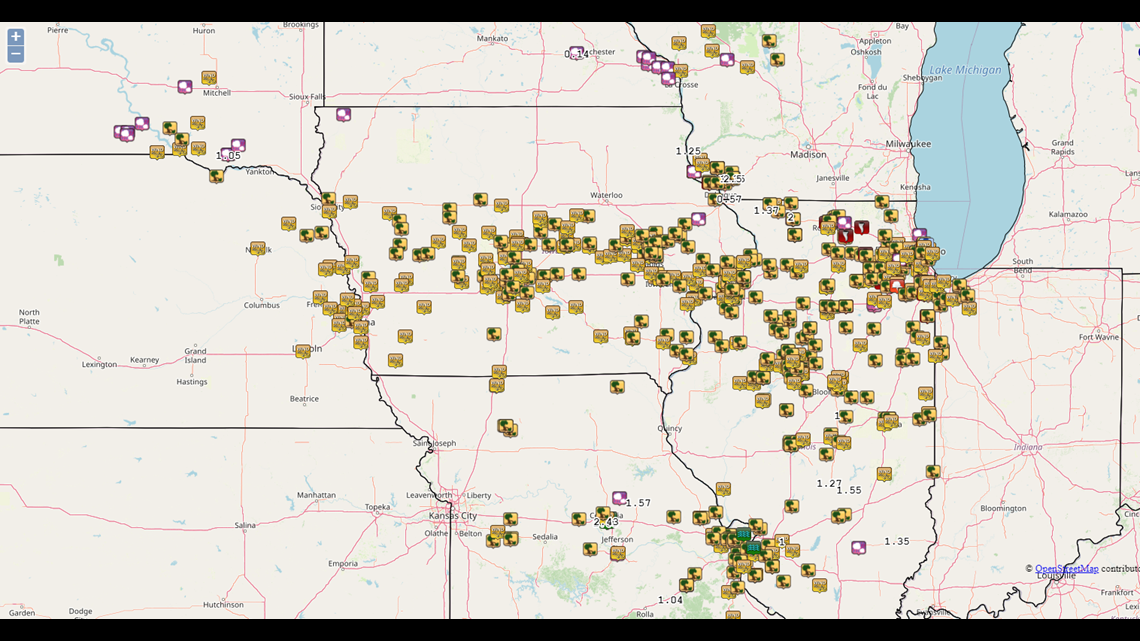

This is a very technical definition and was written more for meteorologists than the general public. With such specific requirements, how can meteorologists predict such an event? While meteorologists know the environment favorable for derecho development, it’s extremely difficult to predict in advance that one will occur. They’re a rare event, as seen in the picture below.

HOW YOU CAN HELP

Before going on, here are various ways you can help Iowans who experienced the hardest impacted of this historic storm.

The Hurricane Misnomer

The frustration over “inland hurricane” may ultimately seem trivial, and something only a meteorologist is concerned with, but in an age where false information runs rampant and demands for truth and clarity are loud, this would seem like an opportunity to clarify and educate. It is also a reminder for news-gathering organizations to double-check with experts if an analogy is truly accurate and acceptable to use.

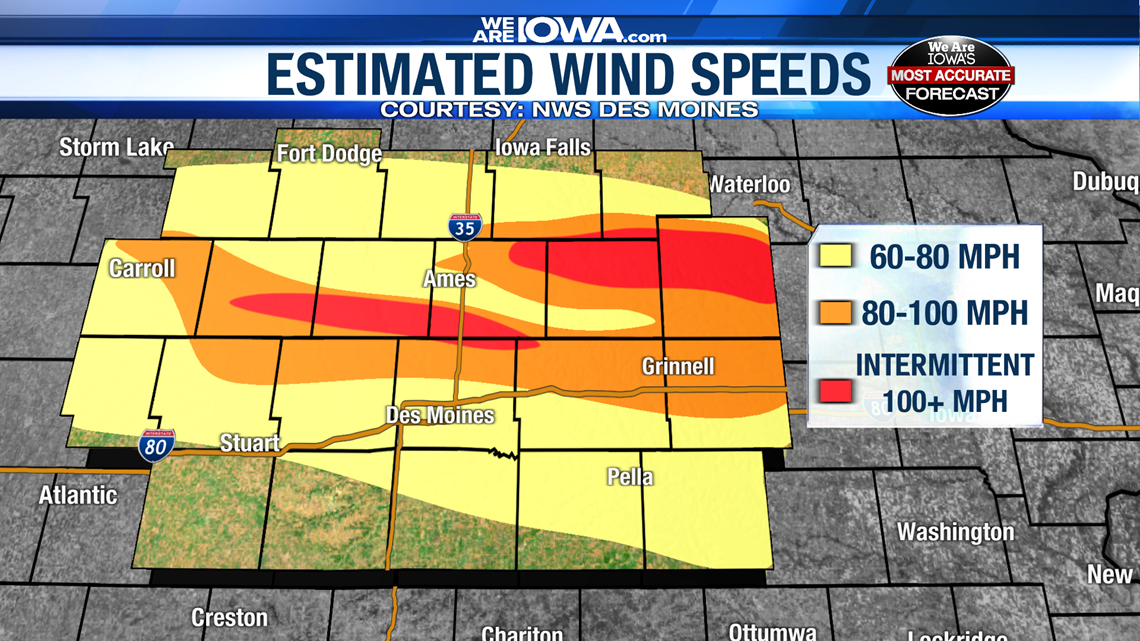

The Midwest derecho has been called an “inland hurricane” because it produced recorded wind speeds upwards of 110 miles per hour. In fact, the highest wind gust reported in Iowa was 112 mph in the community of Midway. While these winds are consistent with a category 2 hurricane, they’re also consistent with an EF1 or EF2 tornado – something Iowa is far more likely to experience.

On the other hand, a hurricane is a type of tropical cyclone. A tropical cyclone, by definition, is “a rotating low-pressure weather system that has organized thunderstorms, but no fronts.” The key word in this definition is rotating. Now, compare the definitions of derecho and tropical cyclone:

Derecho: “a widespread convectively induced straight-line windstorm.”

Tropical cyclone: “a rotating low-pressure weather system that has organized thunderstorms, but no fronts.”

It might seem like semantics, the difference between rotating and straight-line, but it does matter as the two are fundamentally different kinds of weather phenomena. Hurricanes spin, derechos don’t. Compounding this incorrect comparison is the fact it’s been compared to a hurricane at all. There is certainly benefit to putting weather events into perspective, however it doesn’t take an expert to understand that 100+ mph winds are strong and cause damage, so why compare it to a hurricane? Was it necessary? Perhaps it’s the sense of “novelty” of having lived through an event that’s like another. If there was going to be a comparison at all, would it have been better to compare it to a tornado, something the Midwest sees each year?

“There was no warning”

A common message in the aftermath of that destructive Monday storm was that there was “little-to-no warning.” This is technically false, and the idea that there was no warning is perhaps more frustrating to meteorologists than the comparison of an “inland hurricane.”

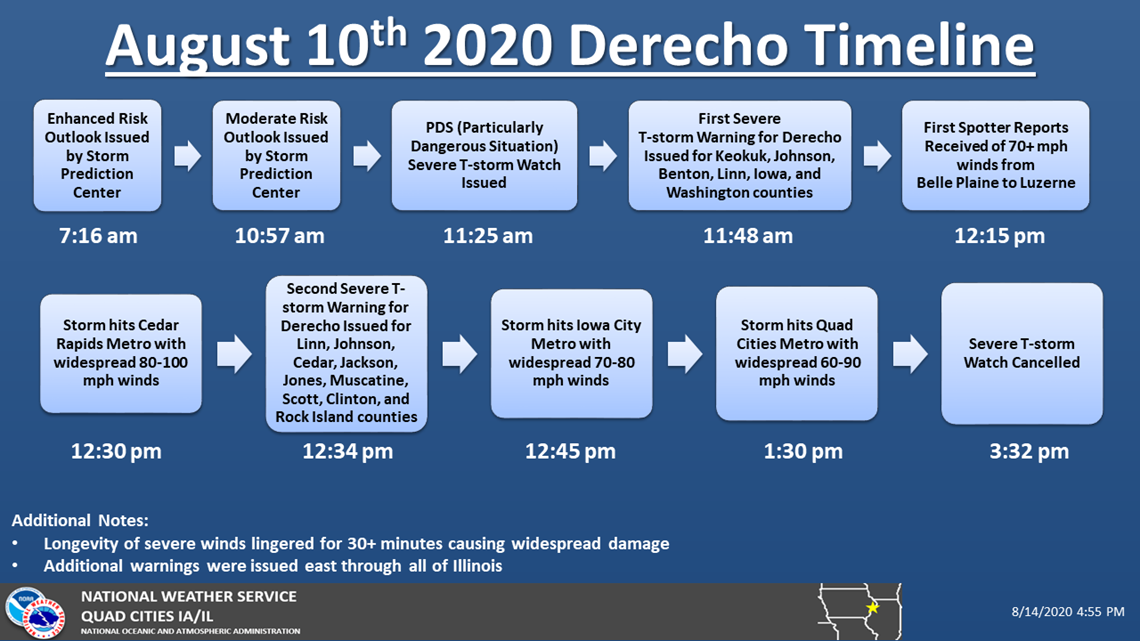

The Storm Prediction Center in Norman, Oklahoma had highlighted the Midwest (for the purposes of this discussion, Iowa) as potential region for severe weather in the days leading up to Monday. The National Weather Service in the Quad Cities provided a nice timeline of events. All times are provided in Central Standard Time.

- At 7:16 a.m., the Storm Prediction Center issued an Enhanced Risk (think of this as level 3 on a scale of 1 to 5 for the potential for severe weather)

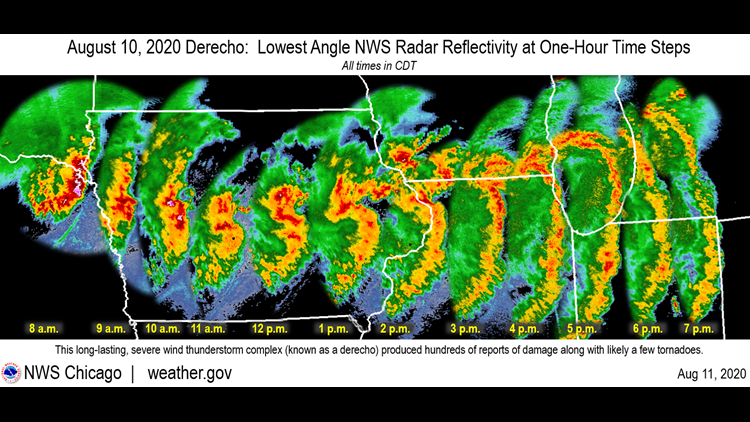

- During the 8 a.m. hour, a bowing line of thunderstorms was crossing the Missouri River into western Iowa)

- A little under four hours later, a Moderate Risk (level 4 of 5) was issued for central Iowa toward the Chicagoland region, indicating increasing concern for significant weather to occur that day as the line of storms in Nebraska began to move into Iowa.

- Around 10:00 a.m., a severe thunderstorm watch had been issued for central and western Iowa. Local media in Des Moines, Sioux City, and Omaha, Nebraska convey these weather alerts when they are issued.

- By 10:15 a.m., the first severe thunderstorm warnings for central Iowa were issued. From here they were issued repeatedly as the line continued to track east.

- Before 11:30 a.m., a “Particularly Dangerous Situation (PDS)” severe thunderstorm watch was issued for central and eastern Iowa. PDS’s are issued when the Storm Predication Center has high confidence in the risk for property-damaging and life-threatening weather.

Let’s pause here. By 11:30 a.m. Monday, we can see there were already several alerts indicating the threat for severe weather that day. As early as 10:00 a.m., severe thunderstorm warnings had been issued with lead times between 30 minutes and 50 minutes – ample time for those ahead of the storm to take necessary shelter precautions. By this time local media had taken over programming to alert the viewing public of the approaching threat. These local media outlets were also broadcasting live on their respective websites and social media pages. While it will be impossible to reach every person, critical weather information was being disseminated to the public – as is required by law. How can this be improved? That is something the meteorological community will need to sort out.

Around 10:45 a.m. the severity of the weather event was established as there had already been tens of thousands of power outages, downed trees, and recorded wind gusts well over 70 miles per hour. New severe thunderstorm warnings issued at this time were providing nearly one hour’s notice of these storms approaching.

The storm continued to gain strength as it marched east across the Hawkeye State. By 12:30 p.m., Cedar Rapids was experiencing win speeds up to 100 miles per hour. More severe thunderstorm warnings had been issued again providing lead times of nearly one hour.

What should we learn from this?

Hindsight is 20/20 and looking back it’s clear there was ample alert days in advance of potentially bad weather, and ample warning the day of. If this is the case, why are so many residents saying they weren’t warned? The issue likely lies less in the public being warned but more in how the public is obtaining their weather information. In this age of abundant information, it’s a bit ironic that so many seem unaware of the forecast. Many get their forecast from an app on their phone, but those apps are not always all-inclusive. Their convenience comes with some limitations. A weather app might not always push a notification of inclement weather. It might say there’s a chance for thunderstorms, but what it likely won’t relay is the specific threat or locations expecting to see severe weather.

Events like the August derecho show that there is a critical lack of weather understanding in the general public. Do meteorologists give the public too much credit for understanding and following the forecast? Perhaps. Meteorology is a complex, inexact science and meteorologists could certainly work toward better educating the public. On the flip side, the public needs to be aware that there is a wealth of reputable sources for a forecast in fair and inclement weather.

It will sound like a self-plug, but events like the Midwest derecho show us that local television is still a crucial communication medium for local events. For weather specifically, nobody will understand the weather of a region better than a local broadcast or National Weather Service meteorologist.

Remember, it is imperative to have numerous ways to receive information about watches and warnings when storms are in the forecast. There are a number of ways to do this: social media updates from a trusted local meteorologist/local news outlet or a NOAA weather radio are the best ways.

More Derecho Information

If you're curious to learn more about this historic storm, the National Weather Service offices in Des Moines, Quad Cities, Central Illinois, and Chicago have very through recaps, videos, images, and analyses.

Alden German (WHAS-TV)

Facebook: /AldenGermanWX | Twitter: @WXAlden

Brandon Lawrence (KCWI-TV)

Facebook: /BrandonLawrenceWX | Twitter: @brandonlaw_wx