ST. LOUIS — Deaths soared, hospitals were overwhelmed and city infrastructure was crumbling: St. Louis was in the midst of a public health crisis in July 1980, one that required the response of the U.S. military.

The cause wasn't a virus-driven pandemic. It was a heat wave that St. Louis now experiences yearly.

The city wasn't a stranger to heat waves by that point. Long periods of extremely high temperatures in 1936 and 1954 killed hundreds of people across St. Louis, the true number of deaths most likely being much higher since officials didn't formally track heat deaths then.

The problem was thought to be a thing of the past in 1980 thanks to air conditioning's growing prevalence. The false sense of security forced city officials to face a reckoning.

Editor's note: The above video aired in 2022.

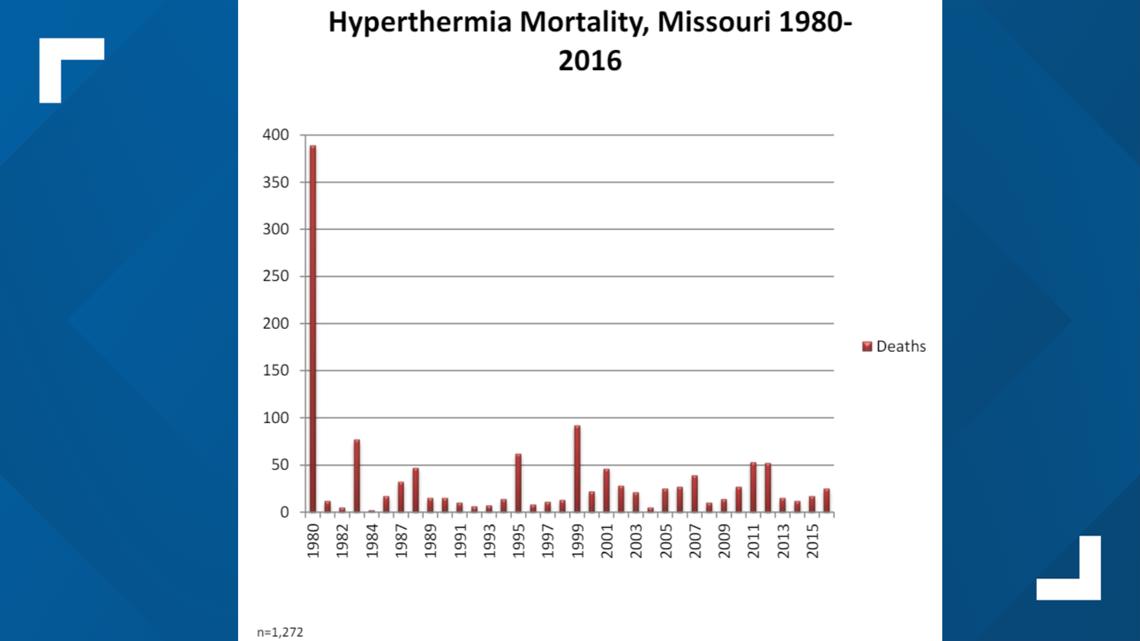

An 18-day stretch of above 100-degree temperatures left nearly 400 people dead across Missouri, with 153 of those being in St. Louis, the vast majority of which were low income, elderly or physically disabled. One out of every 1,000 city residents was hospitalized for or died of a heat-related illness.

The death toll may be hard for modern-day air-conditioned residents to wrap their heads around. But, St. Louis' then-poorly insulated brick-made homes, the majority of which didn't have AC, made the tragedy a near-inevitability.

"After 1980, homeowners started looking for homes with what we would consider modern air conditioning installed," Missouri Historical Society Director of Library & Collections Christopher Gordon said. "The vast majority of houses (during the heatwave) still did not have any kind of cooling, and so one of the things that happened was on July 14, 1980, then-Gov. Teasdale issued a state of emergency and called out the National Guard just so they could distribute fans and conditioners."

Around 200 members of the Missouri National Guard were called into the city to go door-to-door, checking on the health of residents. A Missouri Air National Guard cargo plane airlifted 40 air conditioning units from New York State to St. Louis.

The City's emergency management system was pushed to the breaking point. A system that typically handled around 200 calls a day was getting over 350 calls for help. EMS workers at the city's emergency operations center worked 12 hour shifts to handle the heavy load.

“The 911 system here has been overloaded and we've added two additional lines in here at the emergency operating center to relieve the burden of the 911 system," said one city official.

Hospitals also struggled to keep wards cool. Portable air conditioners were set up at City Hospital where indoor temperatures had been in the 90s.

“I think the critical level has been reduced by the air conditioning units we installed yesterday, and today the very old and very ill patients are now in air conditioning,” one doctor told 5 On Your Side.

Even though it wasn't the city's deadliest heatwave on record, Gordon believes it was by far the heat wave most thoroughly covered by journalists. The tragedy's local media coverage brought a high number of fatalities to residents' TV screens. The incident even picked up national attention.

The in-depth coverage, coupled with air conditioning's existing availability, caused changes nationally and in city programs, Gordon said. The CDC didn't officially start tracking heat-related deaths until after the heat wave. St. Louis adopted several policies toward opening more than 70 cooling shelters around the city. Officials also focused on adding air conditioning to Metro buses, pushed by a large threat from residents of a fare strike.

"It was almost an instantaneous lesson learned," Gordon said. "There was another heat spike in August of 1980, and the death toll was far less … You could turn around, open these shelters and make a difference."

The heat wave was also, in part, what inspired Gentry Trotter to create the Cool Down St. Louis program. The region-wide initiative has been a mainstay in the region for nearly 25 years but started as Trotter's passion to help save lives during times of extreme temperatures.

"People were dying left and right," Trotter said. "Most of us who watched television at that time and read newspapers, we knew we were … going to be facing a long-term problem with heat and getting unseasonable temperatures. When I saw these deaths … I was worried and wondering what we can do."

Trotter's labor of love went on to help countless people across the St. Louis region access and afford air conditioning. The organization is holding its annual beat the heat event Tuesday morning, giving away 800 Energy Star-certified window air conditioners and 100 smart thermostats to seniors, people with disabilities and low-income residents.

Find out more about the program on Cool Down St. Louis' website here.

Top St. Louis headlines

Get the latest news and details throughout the St. Louis area from 5 On Your Side broadcasts here.