ST. LOUIS — One woman, Mary Meachum, helped facilitate multiple trips out of the St. Louis area for the sake of freedom. In the mid 1800s, enslaved people fled Missouri in an attempt to reach the free state of Illinois.

5 On Your Side visited the site of one of the most famous escape attempts that Meachum was tied to. We know that Meachum was a free and prominent black woman living in St. Louis in the mid 1800s. She was also an abolitionist and conductor of the Underground Railroad.

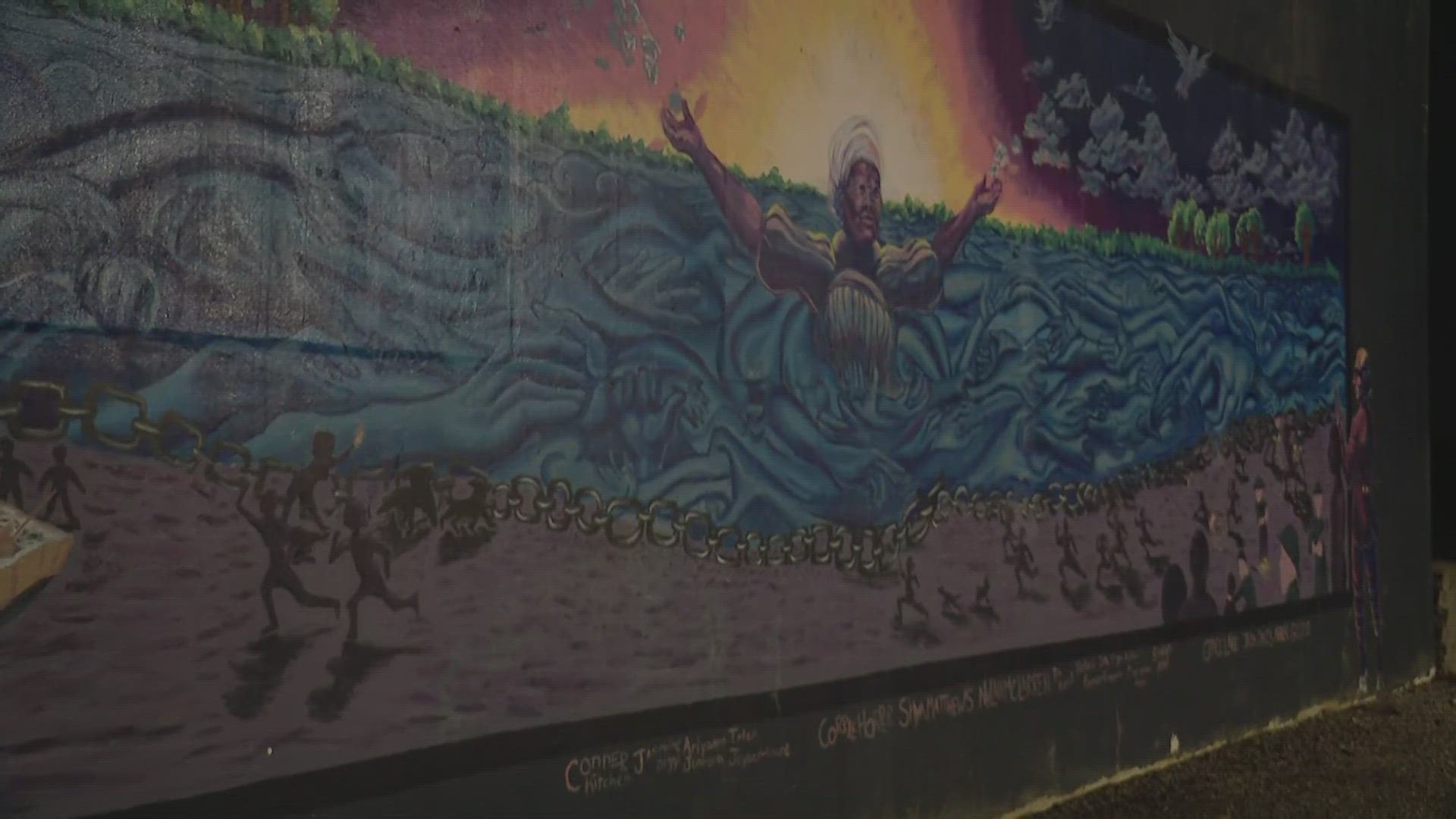

Today the area along the Mississippi Riverfront near North Riverfront Park is known as the "Mary Meachum Freedom Crossing," a nationally recognized historical site.

But, in May, 1855, it was the spot where a small group of slaves entered the Mississippi River to reach freedom on the other side of the river in Illinois.

Our reporter, Sydney Stallworth, met with Angela DaSilva, a cultural preservationist and former professor at the historic site. As they stood overlooking the river, DaSilva asked our reporter, "You see how fast that river is moving. Do you think you could swim across it to the other side? Would you even try?"

When the terror you’re running from outweighs the terror you’re running to... try, you might.

DaSilva said, “That river is both boundary and horizon.”

In Antebellum America, this gateway to freedom took the form of a deadly obstacle for slaves living in Missouri. Over in Illinois, the river served as a constant reminder of the horror that lies just beyond the horizon.

Meachum and her husband John Berry Meachum established the First African Baptist Church, the first Black congregation in St. Louis.

DaSilva said, “Free Blacks would be sitting in silks and satins next to somebody who’s got broadcloth on and is enslaved.”

In 1847, Missouri outlawed the education of all black and mixed race people. The Meachums taught both enslaved and free men to read and write in secret, in the basement underneath their church. The two also opened a makeshift school aboard a boat docked in the federally-regulated Mississippi River, floating just outside the state’s jurisdiction. As conductors of the Underground Railroad, the couple educated slaves then would send them on to freedom.

DaSilva said, “They owned a farm in West Alton, Illinois. That would have been a waypoint, I’m sure, between here and Alton to move people.”

Even after her husband’s death, Meachum continued to help slaves find freedom in secret and by utilizing legal avenues.

“From the time he died to the time she died, she posted surety bonds for 5 individuals to stay in Missouri. They are $1,000 a piece," DaSilva said. "This isn’t with her husband’s aid… this is what she did.”

According to DaSilva, freedom papers didn’t provide much protection.

“Stealing free black people off the street and selling them into slavery was a business.” She said, “Black skin carried with it the presumption of slavery. You had to prove that you weren’t.”

Under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, slaves were required to be returned to their owners, even if they’d escaped to a free state. Slave catching was the law of the land.

DaSilva said, “The penalties for aiding and abetting were horrible.”

On May 21, 1855. Meachum organized a trip for about 8-10 enslaved people to cross the Mississippi River into Illinois.

The word got out, and at least five people were caught by police and slave catchers.

DaSilva said, "She was arrested. She wasn’t here at the site. She was at home … Thirty years I’ve been studying this. The book down at the circuit court that has the deposition when it went to trial-- those pages are torn out. So we really don’t know, but we know she never served a day.” She said, "... after this event, she stopped, because now-- she was being watched.”

Meachum's underground work shifted to making change on the surface of St. Louis streets.

She ended up integrating the city’s horse-drawn omni-bus during the Civil War, and helped educate black soldiers stationed at St. Louis’s largest military base.

DaSilva said, “With the Union Army help, Mary Meachum sued and the city capitulated. Black women could ride on Saturdays to be able to teach these men how to read and write.”

Our reporter walked along the riverfront with DaSilva, retracing the steps to freedom taken on this path with footprints left behind by DaSilva’s own ancestors.

DaSilva tells Stallworth, “I know where five generations of my enslaved family are buried. Right here in Missouri-- both sides."

DaSilva speaks about resilience and said “It’s amazing to me… absolutely amazing.”