ST. LOUIS — It took a tragedy for St. Louis to get serious about heat resilience. It may take another to remind the city what's at stake.

Heat-related deaths largely went under the radar before the heatwave of 1980. Sweltering temperatures left nearly 400 people dead across Missouri, with 153 of those being in St. Louis, 70% of whom were elderly, physically disabled, or low-income. One out of every 1,000 city residents was hospitalized for or died of a heat-related illness as the city's temperatures soared above 100 degrees for 18 days.

The city, in response, quickly put numerous social programs in place focused on distributing air conditioners and setting up cooling centers. Many of those programs are still in place, but needs and costs continue to increase.

The St. Louis region now sees the same temperatures that caused the 1980 tragedy every summer, due to human-driven climate change through the burning of fossil fuels like coal, oil and gas. Hundreds of thousands face difficulties paying their utility bills at any given time, with cooling groups calling air condition demand "unprecedented." With heat expected to worsen, are the city's previous strategies enough to save the most vulnerable of city residents?

RELATED: 'A quality of life issue': Number of Missourians without air conditioning soars amid record heat

St. Louis' coming heat intensity shift

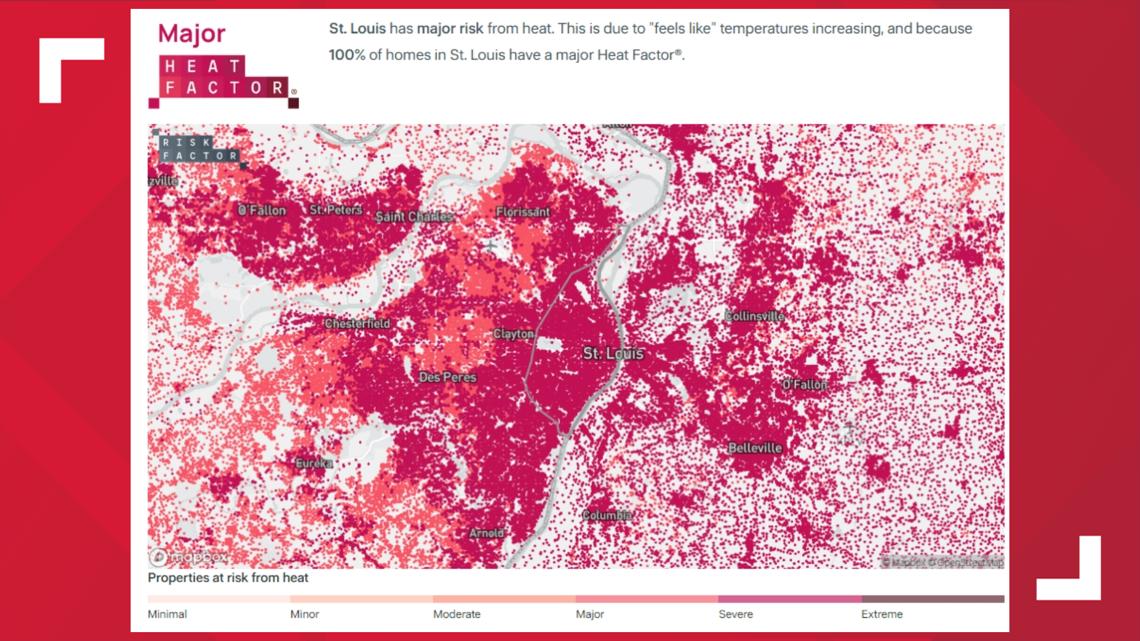

Enter "St. Louis" into Risk Factor's search bar, and you will see a sea of red.

The climate-risk mapping website projects all of St. Louis' properties to have a "major" heat factor, meaning 100% of the region's properties have a high risk of exposure to dangerous heat over a 30-year mortgage.

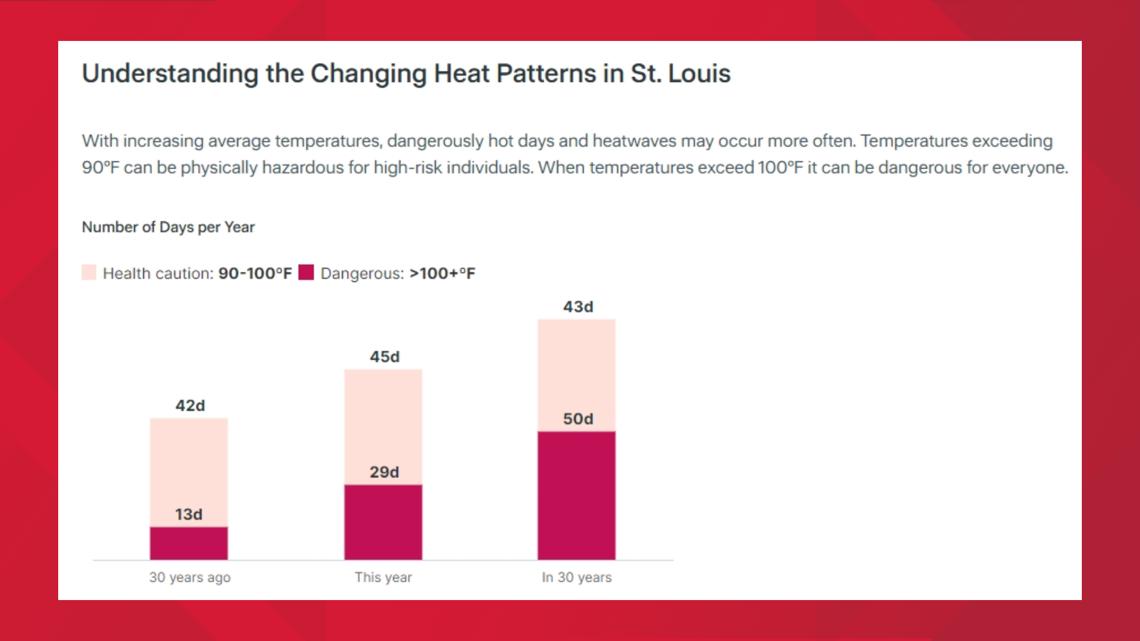

The projection is largely based on how heat is expected to increase in the area. The same kind of heat wave that killed 400 people in Missouri is now seen frequently and worse, with the St. Louis region experiencing an average of 30 days with a "feels like" temperature above 100 degrees annually. In 30 years, the region is expected to see 50 days with a "feels like" temperature above 100 degrees annually.

"It's a heat-intensity shift," said Jeremy Hoffman with Groundwork USA, a climate scientist who collaborated with Risk Factor on their heat risk model.

"The last couple of summers, we've seen a concentration of extremely high temperatures in this particular part of the country ... they identified this 'heat belt' in central-southern Midwest that just gets hammered by these intensity increases."

While St. Louis is expected to see many more extreme heat days, the number of days the region sees with a "feels like" temperature between 90 and 100 degrees is expected to stay the same. Hoffman said this will most likely materialize as hotter days happening earlier in the spring and later in the fall, while extreme temperatures make up the summers.

Missouri's State Climatologist, Zack Leasor, agreed with Risk Factor's assessment, saying the findings mirror the trends seen in Missouri and St. Louis' climate historical records dating back to 1900.

"We've seen an overall warming trend in our temperatures," Leasor said. "Statewide, our average daily highs have really only slightly increased, but our daily low temperatures have increased two degrees over the last 100 years ... during these heat events, our lows are not cooling off at all."

Warmer overnight temperatures greatly increase heat health risks in humans, especially among elderly and low-income populations which were the main victims of the 1980 heatwave. The trend is worsened in St. Louis due to the prevalence of heat-absorbing concrete and asphalt, making temperatures even hotter for city residents.

If temperatures don't cool down overnight, people without air conditioning or who have been disconnected from electricity due to not being able to pay their utility bills won't be able to find relief, an increasing trend in St. Louis.

'It's very hard to live here': Residents' continual struggle to stay cool

The St. Louis region may have created numerous heat-focused policies after the tragic heatwave of 1980, but many of those programs are beginning to lag behind excessive demand.

Even though the initial response to the 1980 heat wave appeared robust, researchers said the same solutions could have been implemented much earlier if officials had paid attention to the needs of the city's most vulnerable.

"Conditions similar to 1980 have occurred ten times since 1911, with the most recent heat wave prior to 1980 occurring in 1966," researcher R.S. Allexenberg said in a 1981 study. "The long periods between crises have caused medical and social planners to neglect or overlook preparations for heat-related illness. Consequently, each new government and medical generation has to deal with these crises from 'scratch'."

The city and state's current leadership appears to be caught in the same "from scratch" pattern. The city created more than 70 cooling centers in the wake of 1980's nearly 400 heat-related deaths, but that total has dropped to 17 thanks to a widespread increase in residential air conditioning.

An average of 205,000 Missourians are currently behind on their utility bills at any given time and are at risk of being disconnected, according to Ameren Missouri data. Increasing heat means rising utility charges, forcing vulnerable residents to choose between paying for air conditioning, rent, or food.

“It's very hard to live here," Central West End resident Robert Woods previously told 5 On Your Side after his air conditioner broke and required $5,000 worth of repairs. He says he doesn't have anywhere else to go.

PREVIOUS COVERAGE: More than 200,000 Missourians are at risk of losing electricity. Ameren won't say how it decides who to cut off

Gentry Trotter, founder of the Cool Down St. Louis program that provides free air conditioning and utility assistance to elderly, low-income and physically disabled residents, said he doesn't see need decreasing anytime soon.

"I can predict to you that it's going to get worse," Trotter said. "We're just bandaid, bandaid, bandaid. The more money we can get, the more the federal government understands, the more the public understands, the more corporations understand that being without an air conditioner in the middle of a dead summer is a public health and safety issue."

Looking at the projected heat increases for St. Louis, Hoffman said it will take a lot more than just air conditioning to keep the city cool. St. Louis and other cities across the country will have to mitigate heat, through increasing shade, green spaces and water features, while also managing heat by preparing for increased emergency room visits and establishing plans for water distribution and heat education materials.

"It's really the combination of reducing the burden of heat while also coordinating among what would otherwise be siloed city departments to work together and minimize the strain on the system that ultimately exacerbates mortality," Hoffman said.

Top St. Louis headlines

Get the latest news and details throughout the St. Louis area from 5 On Your Side broadcasts here.